about:

the concrete gaze (2021) was an independent research project that I developed and curated for BA CCC’s London Project.

the concrete gaze: reclaiming autonomy through cooperative merchandising, attempts to address the feeling of detachment that can arise when living in a historic and significant work of architecture. Often with popular pieces of architecture, specifically Brutalist social housing, creatives unknowingly produce illustrations that aestheticise and ‘misrepresent’ the experiences of people who live in these estates (Brennan, 2015).

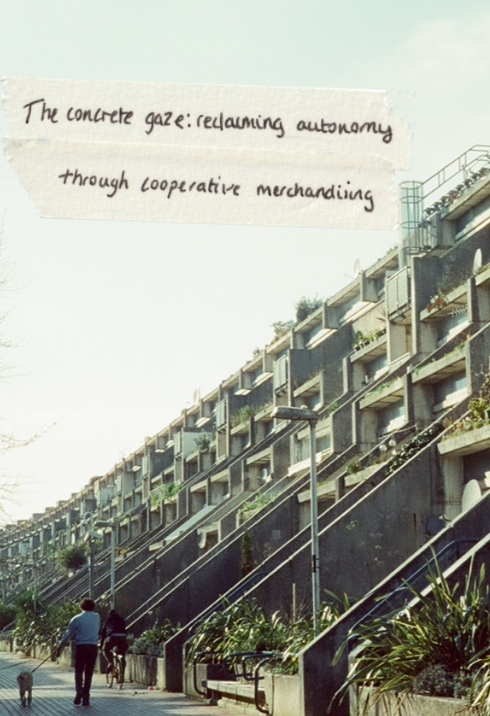

A growing trend towards postwar housing has left a gap in the market for the cooperative merchandising of these estates. With flocks of Brutalist fanatics visiting architectural gems like the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate every year, I thought it could be interesting to market the landmark in a way that benefits and involves the community.

Over the years, the Alexandra and Ainsworth Estate in Camden has featured in numerous blockbuster films such as Kingsman: The Secret Service (2014), the BBC's adaptation of Love, Nina (2016) and the BBC's pre-apocalyptic drama series Hard Sun (2018). The success of these films, along with the architecture’s dystopian quality, has only made the estate more popular, with thousands of tourists visiting every year (Swenarton, 2014).

The aestheticization of postwar housing has provided a unique opportunity to work with members of the Alexandra Road community to develop a series of architectural based merchandise that will be sold online and at art and design stores across London.

Through a string of workshops, the youth centre on the Alexandra Road Estate work with industry experts to create their own merchandise, including tote bags, tea towels and art prints. All of the profits made from the merchandise will fund the youth centre and other community initiatives.

Jessie Brennan's Regeneration! (2015) project with the residents of Robin Hood Gardens has inspired the participatory aspect of this project (Brennan, 2015). It would have been easy to start designing my own merchandise featuring the Alexandra Road's iconic architecture - I could have easily taken this approach and just donated the profits to the estate. However, Brennan's approach is experientially based and raises questions around the social aspect of regeneration. This inspired me to collaborate closely with the residents so that the project could be more meaningful and resident-led and so that I could raise relevant questions surrounding the aestheticization and commercialisation of postwar social housing.

By merging ideas from curator to resident, we will be able to produce a series of carefully designed merchandise that reflects the community feel of the Alexandra Road Estate. The project makes a conscious effort to avoid 'distorting the realities' of the people who live postwar social housing, despite its architectural aestheticization (Halnon, 2002).

The postwar housing phenomenon is not limited to London, but this particular architecture is very specific to London's social housing history. In the 1960s and 70s, the London Borough of Camden had a very progressive architecture department. Sydney Cook, the director of housing, protested the government's high-rise building scheme and appointed the architect Neave Brown to deliver a series of low-rise and high-density developments which came to be very successful (Swenarton, 2020).

The collapse of the 22-storey tower block Ronan Point in 1968 spawned new ideas about the city's configuration. Tower blocks surrounded by public open space were no longer fit for purpose, and the ziggurat style terraces of Neave Brown’s Alexandra and Ainsworth estate redefined low-rise, high-density social housing in London. This style of building is similar to the Brunswick Centre (1972) by Patrick Hodgkinson and St George's Fields (1976) by Design 5 (Melhuish, 2005). However, Brown was committed to making decent social housing to improve the experience of the city, while the Brunswick Centre and St George's Fields were built with private ownership intent.